As time grows short, twin hopes to find brother's body

Vincent and Richard Krepps served together in Korean War, but Richard died in captivity

Twins Vincent and Richard Krepps enlisted in the Army together in 1949, and went to war the following year.

Cpl. Vincent Krepps endured gunfire in Korea, lost nerve, earned a Silver Star. Then he went home.

He left his brother behind.

When he reached his parents' house in Essex in spring of 1951, there were hugs and handshakes and the question that had no answer.

Dickie?

Cpl. Richard “Dickie” Krepps starved to death in a North Korean prison camp. He was too weak to swallow spoonfuls of barley from the soldier imprisoned beside him.

It was snowy, his neighbor would say, and the dead were stacked outside like cordwood.

For 65 years and five months, Vincent Krepps has searched for his brother's body. This Memorial Day, he's still looking.

The search has sent him back to the hills of North Korea with their graves. His clues fill 13 binders in the closet of his Parkville apartment. He has emerged as an advocate for families of the 7,800 Americans still missing from the Korean War.

Methods for identifying the bones of service members have improved in the decades since the Korean War. Last year, using DNA analysis and other methods, the military identified 73 Americans missing in foreign wars, 35 of them in the Korea War.

This month alone saw burials of Army Cpl. David Wishon Jr. of Baltimore, who was 18 when he went missing in Korea in 1950, and Navy Chief Petty Officer Albert Hayden of Southern Maryland, who was 44 when he was killed in the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Hope for more identifications is growing. But for Vincent Krepps, time is growing short. He turned 85 this month.

Today, at the annual Memorial Day service at Dulaney Valley Memorial Gardens in Timonium, he will tell of his search — his final mission. And he will ask something of the crowd.

Following clues

The Korean War — the three-year conflict sometimes called the forgotten war, sandwiched between World War II and Vietnam — began in June 1950, when North Korea invaded South Korea.

The United Nations backed South Korea, and the United States deployed hundreds of thousands of troops; China backed North Korea. The sides fought to a stalemate, and signed an armistice in 1953.

Richard Krepps went missing Dec. 1, 1950, after the Chinese poured across the Yalu River into North Korea and overwhelmed U.S. troops.

Vincent wasn't there. He had been hospitalized after a truck crash. He returned to the brothers' artillery battery to learn Richard had disappeared.

Richard Krepps was last seen scrambling toward a hill, gunfire everywhere.

Vincent and Richard Krepps had never before been apart.

The twins — Vincent was two minutes older — had shared a bed through childhood. Both left-handed, they carried penknives and wore matching Waltham wristwatches. Richard was better pitching homemade baseballs of tape and string. They spent summer nights at the Dairy Queen playing the nickelodeon.

They endured basic training side by side, then reported together to Battery D of the 82nd Antiaircraft Artillery AW Battalion, 2nd Infantry Division.

In Essex, Vincent Krepps struggled to return to normal life. Nights were the worst; the enemy emerged from shadows. Hail against tin sounded like the wrenching patter of gunfire on tank armor.

He was assigned hospital duty at Fort Meade, feeding and bathing the wounded. The newspapers carried a photo of a bleak North Korean prison camp. Among the haggard prisoners was Richard, his eyes downcast.

With the armistice of July 27, 1953, the sides exchanged thousands of prisoners. Some men from the Krepps brothers' unit arrived in Valley Forge, Pa. Vincent Krepps and his mother went there for answers; she waited outside.

“I'm sorry,” a master sergeant told him, Krepps wrote in a memoir. “I heard he died, but I don't know for sure.”

Mother and son drove in silence back to Essex.

“Maybe it would have been less painful for my entire family if someone there would have told me they saw Richard die,” Vincent wrote in the memoir, “One Came Home.”

Without answers, their hopes and fears persisted.

In January 1954, an Army notice arrived: Cpl. Richard Warren Krepps was declared dead.

The Army presented evidence. Cpl. James Burdelas said he heard Richard suffered mental illness and died at prison camp in August or September 1951. Cpl. William Zollenhoffer stated he heard Richard died near the Yalu River five months earlier in March. The North Koreans reported Richard died in June 1951 from pellagra, a disease of malnutrition.

The contradictions gnawed at Krepps. He swore he would see his brother home.

It seemed hopeless. But it had seemed hopeless, too, that day in Korea when he went for help, barreling down the road alone in his light tank, North Koreans firing from the hills, a single grenade gripped in his lap, and the crying, grateful, mad rush when he reached the lieutenant colonel to say men were trapped in the hills.

His “gallantry in action” that day earned the Silver Star.

In Essex, Vincent spent months writing to former prisoners from his unit, eventually 45 men. Their letters returned without answers through the 1990s.

By then he was editing the Korean War veterans magazine, “The Graybeards.”

In May 1997, families were permitted to address a North Korean delegation visiting New York. U.S. officials had been negotiating access to the battlefield graves. Vincent printed his remarks in his book.

“I saw [your soldiers] as human beings and felt their pain. I feel you must have had men that felt the same,” he said. “We have another chance to show our feelings again by helping our loved ones from both sides come home.”

The week, however, ended without agreement. Thousands of Americans were still missing.

In October 1998, Krepps flew to China and North Korea with veterans and military officials to appeal again for information. Tensions with North Korea continued to interfere with the recovery. Now the visitors and their hosts toasted to peace.

“We will find your brother,” a North Korean told him.

Vincent rode to the hills where North Korean

“They didn't tell us anything in China or in Korea that really nailed down any one person,” Krepps

Two more months passed before Krepps

The letter from Nevada was dated Dec. 1, 1998. The writer began: “Your brother and I were captured on the same date as it is this very day.”

Ronald Lovejoy was the soldier, withered to 78 pounds, beside Richard at the prison camp in the snow. It was a temple that the North Koreans were calling a hospital, he wrote

Richard wouldn't talk, Lovejoy wrote.

He died, Lovejoy wrote.

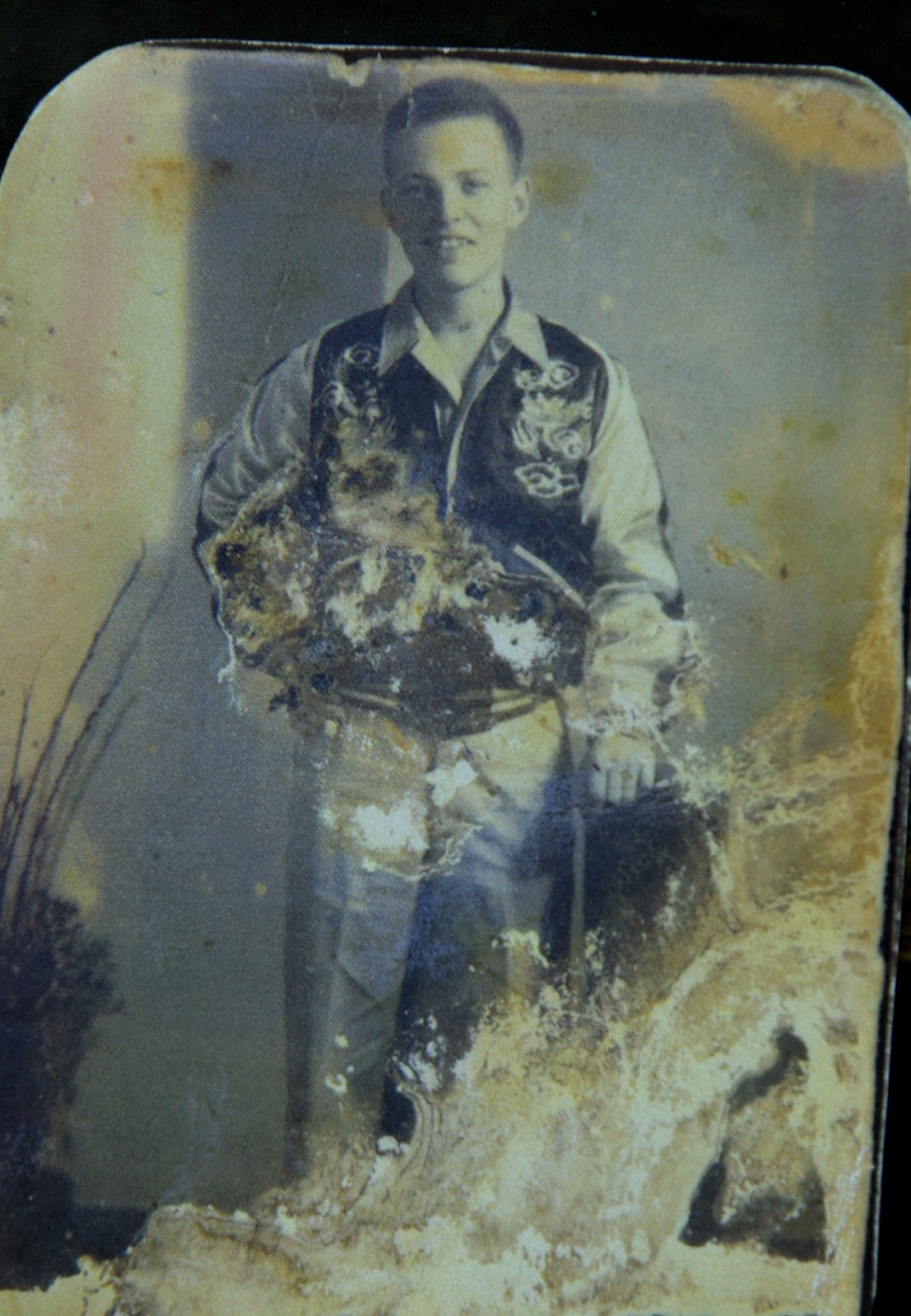

Vincent might have dismissed it as another rumor, but for the photo Lovejoy saved all these years: astained Army picture of Richard smiling, hand on his hip, just a boy.

A brother's request

Krepps'

Perhaps someday, Vincent will add photos of a burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

“That's the final stage of the war for me,” he said. “That Richard comes home and I'll be alive to go to Arlington and see his final location …

“Maybe I'm thinking crazy.”

But military researchers found Wishon Jr. He was buried in early May at Arlington. And they found Hayden, one of the first Americans killed in World War II, and buried two weeks ago near Mechanicsville.

Families across the country have submitted DNA by cheek swabs to a database for matching. Krepps has, too. About 90 researchers are working at labs in Hawaii, Nebraska and Ohio to identify the bones of Americans returned from overseas.

Last year, they identified 73; up from 69 the year before, and 60 the year before that.

Still, the recovery has fallen short of expectations. Congress has ordered the military to make 200 identifications annually by fiscal year 2015. But that target has proved elusive.

The Government Accountability Office reported in 2013 that the effort was undermined by “leadership weaknesses” and a “fragmented organizational structure.”

John Zimmerlee, director of the private Korean & Cold War POW/MIA Network, goes further.

“Our government is strongly aware of a number of previous misidentifications,” he said. “Families who received Johnny's remains 65 years ago will now be told that it wasn't Johnny because a recently exhumed body is actually Johnny.”

In Marietta, Ga., Zimmerlee has amassed a database of records on Korean War prisoners. He said remains of three unidentified soldiers from the same prison camp as Richard Krepps are buried among unknowns in the National Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii.

Vincent Krepps said he would ask officials about the three: N-14464, N-14473 and N-14493. But he doesn't dwell on the agency's record.

“I assume they're doing their job,” he said. “They got a hard problem.”

Since the GAO report, commanders have consolidated different elements into the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

The aim, spokesman Lee Tucker said, is “to more effectively increase the number of missing service personnel accounted for and ensure timely and accurate information is communicated to their families.”

Technology is helping. The practice of washing bones in formaldehyde once put them beyond the reach of DNA testing. Now advanced techniques allow researchers to extract DNA from those remains.

They also have discovered that clavicles — collarbones — are unique, like fingerprints. The military has thousands of chest X-rays from tuberculosis screenings.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency is on pace to reach 200 identifications this fiscal year, Tucker said.

“There are no closed cases,” he said. “If we're not able to identify all the individuals today, it doesn't mean that someday we won't be able to.”

Vincent's wife of 53 years, Susan, died after a fall last year. Now he feels the urgency of his age.

“If it takes 20 years, that has to improve,” he said. “They promised us a couple hundred identifications a year. That hasn't come true. Everything they promised doesn't always come true.”

He paused.

“But it gives you hope.”

Sometimes, he dwells on it: Maybe he should have been imprisoned in the camp, too. Maybe he could have made Richard eat. Maybe he could have saved him.

“I just wish I was around him for all this time,” he said. “I'd have had a good friendship, and I'd have had somebody to talk to.”

Krepps shares the apartment with his poodle, Sara. The grandfather clock chimes. Miles away, even now, technicians are trying to match names to the bones.

Vincent wears his blazer to dinner. He walks easily down the hall to the Oak Crest dining room. Decades of searching, he says, have kept him active.

But sometimes his thoughts wander. So he scripted his remarks for Memorial Day. He will tell of twin boys who went to war, and one who came home. And he will ask something of the crowd — something for his brother.

“I am the closest family member left,” he'll say. “So when Richard comes home, and if I am not here, please welcome him back.”