Ravens

All in

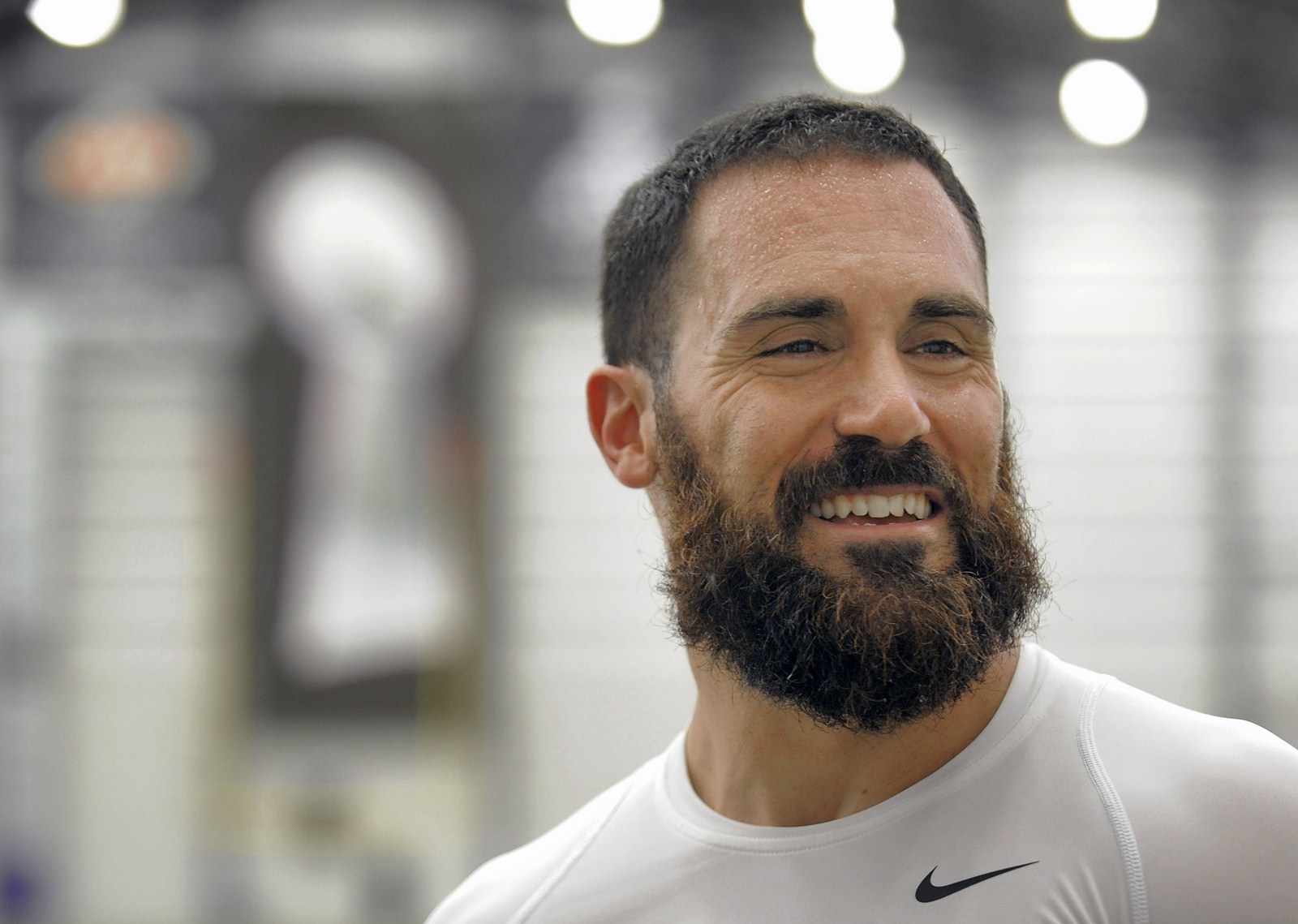

Safety Eric Weddle brings his old resolve to his new team

Eric Weddle's eyes gleam, and he greets your extended hand with a fierce grip. “Why strive to be average?” he says, and you know he's talking about this and every other moment in his day.

The Ravens and their fans hope Weddle will stabilize an erratic secondary and be the sort of playmaking safety the team has lacked since Ed Reed departed after the 2012 season.

What they're getting for sure is a 31-year-old two-time All-Pro who seems delighted to prove himself all over again after a miserable final season with the San Diego Chargers, whose management seemingly no longer wanted him.

The spark never leaves his eyes and the eagerness never fades from his voice as he describes his introduction to the Ravens and his family's impending arrival to a new home in Baltimore County.

“The Weddles dive in,” he says. “We're all in, whatever we do.”

Here's what “all in” means for Eric Weddle:

It means he committed to a new religion and a lifetime with the woman he adored at an age when most of his peers were goofing off at college beerfests.

It means arriving at his team's practice facility before dawn and staying up to watch game film with his wife, Chanel, after their four kids have gone to bed.

It means dog-piling on top of a new teammate to celebrate an interception in a meaningless summer practice.

It means texting with his college coach about the nuts and bolts of Saturday game plans years after he graduated to professional stardom.

It means moving his family members across the country when they had just broken ground on their dream house in Southern California, where Eric and Chanel both grew up.

“He's the best human being I've ever met in my life,” said his agent and close friend, David Canter. “He signs every autograph and poses for every picture. He's got a group of friends that goes 40 deep, and they'll all tell you he's never changed. He's a man of extreme conviction.”

Asked what he's enjoyed most about getting to know the safety, Ravens coach John Harbaugh pointed to the depth of Weddle's commitment.

“He's got an enthusiasm for the workday,” Harbaugh said. “He loves every part of the workday. He loves every part of being in here and being a football player. There's never something that you look at him and he's not excited to do. That is infectious.”

Weddle's eagerness is so persistent — No.?32 seems to pat a teammate on the shoulder or offer a word of encouragement after literally every play — you could imagine him being a coach's favorite and an annoyance to his peers.

But that's far from the case, current and former teammates say.

“He was ‘The Man,' the voice of our defense,” said former Ravens linebacker Jarret Johnson, who played three seasons with Weddle on the Chargers. “His routine, his pace — it's a triathlete's pace. It's ridiculous. Sometimes I'd say to him, ‘Hey, man, you've got to slow down a little.' But it works for him.”

Weddle said he sensed teammates taking the measure of him in the weeks after he signed his four-year, $26 million deal with the Ravens in March.

“It took them awhile to figure out, ‘Is this the real Eric?'?” he said. “Because I'm always helping them, I'm always there for them. That's who I am. I get more appreciation, more love, more energy when someone else makes a play than when I do.”

Lardarius Webb, who will pair with Weddle at safety, says the Ravens don't want their new star to tone it down a bit.

“A leader,” Webb says when asked his early impressions. “I told him, ‘We want Eric Weddle. Don't hold back. Don't be quiet. We want you. If you yelled when you were with the Chargers, I want you coming out here yelling. Just be yourself. Grow the beard back, because we want the beard. If that's who you were, grow the beard.'?”

Ah, the beard — a chin bush frizzy enough to make a folk singer proud. Weddle shaved it as a sign of the rebirth he'd experience with his new team. Chanel was thrilled to get a clean glimpse at her husband's handsome features. But fans and teammates weren't buying smooth-faced Weddle. So the regrowth has begun, with a purple dye job looming in the fall.

Growing up with conviction

Weddle carried a whiff of destiny even before he was born. His mother, Debbie, awoke one night during the second trimester of her pregnancy and realized she was lying in a puddle of amniotic fluid. After a frantic trip to the hospital, doctors told her to steel herself for an inevitable miscarriage.

She and her husband, Steve, waited through a tense week at the hospital and then a month of bed rest at their home in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif., about 90 minutes north of San Diego. But the baby's heartbeat never weakened, and the pregnancy proceeded normally, in defiance of all predictions. Eric Weddle was born a few months later at a robust 7 pounds, 8 ounces.

His all in personality took little time to manifest itself. When the Weddles went camping in Baja, little Eric inevitably walked to the edge of the steepest cliffs. “Just to scare the daylights out of us,” said his mother, a kindergarten and first-grade teacher for 39 years. “He had no fear of anything.”

Weddle started T-ball at age 5 and was a multisport star from first grade on. He was most gifted at baseball and most passionate about basketball (he still hooped in recreational leagues while with the Chargers and shoots jumpers to pass time at the Ravens facility). But he found a sense of communion in football, bringing carloads of boys to the family home to watch the game tapes his mother shot as far back as Pop Warner.

He's still pals with a lot of those guys, taking them to Las Vegas for a weekend every offseason.

Though Weddle accumulated bags full of recruiting letters from Pac-12 powers, the interest fell away as his senior year approached. He committed to Utah — which had just hired a young coach named Urban Meyer — because he didn't have many other options.

Meyer was skeptical when he laid eyes on the modestly built, 5-foot-11 recruit. “He had every reason to be,” said Kyle Whittingham, an assistant at the time and now Utah's head coach. “Eric looked like 1,000 other high school kids.”

But Whittingham was sold on Weddle's rare athletic ability and aptitude for the sport, and he told Meyer so. Weddle, whose outspoken confidence shocked some upperclassmen, quickly proved him right, becoming the star of his class.

After that season, his instincts steered him to another major life decision — conversion to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He was 19.

“I was wanting something, feeling like there was something out there for me,” Weddle says. “I just ventured out and it felt right. It's been one of the best decisions, if not the best decision, I ever made. It's given me clarity, given me direction on this life, what I'm about, what I need to do, where my focus should be.”

Weddle drove all night through a snowstorm to tell his Lutheran parents of his impending conversion. They were taken aback.

“Will we be included in your life?” his mother asked.

“Of course,” he said. “I am who I am because of you.”

Weddle takes his faith seriously enough that he always finds a Mormon temple to attend before he goes to the stadium on Sunday, even when on the road. He's missed team buses on a few occasions in favor of taking the sacrament.

Though it wasn't a motivating factor at the time, the commitment to Utah also took him closer to Chanel, who played soccer at Utah State. She was a year ahead of him, but they had dated in high school before falling out of regular contact.

She was at a tournament in Idaho when she saw her old boyfriend on television, hobbling on crutches because of a sprained knee. She texted him and, less than a year later, they married.

Again, Weddle drove through the night to inform his parents of a massive life decision.

“Both sets of parents kept offering us more money if we would just wait for a year,” Chanel recalled with a laugh.

As usual, there was no dissuading Eric. “He was always that way,” his mother said. “If he put his mind to something, that was it.”

He and Chanel lived between their respective campuses, rarely seeing each other during the week because of their long commutes. They sometimes had just a few hundred dollars in their bank account, and a big night out consisted of bowling and barbecue with friends.

“But we had the time of our lives,” Weddle said.

He can't fathom what his teammates go through, trying to meet future wives while they're playing in the NFL — even if Chanel zings him as sharply as anyone when she spots him messing up during their nighttime film sessions.

A star's rise and falling out

Even as he was establishing a lifetime course of faith and family, Weddle became something of a folk hero in Utah's blossoming football program.

“He's one of the most popular players to ever come through here,” said Whittingham, who still trades detailed texts with Weddle about Utah's current team.

When Canter, Weddle's future agent, traveled to Salt Lake City for a scouting expedition, he quickly noticed kids toting “Weddle for Heisman” signs. At the time, the diminutive Ute played seven positions across both sides of the ball and got the crowd chanting “Weddle! Weddle!” as he took a series of direct snaps at wildcat quarterback to run out the clock in a victory. It was a Hollywood scene.

Canter turned to an associate and said, “I don't know what we have to do, but we have to get this guy as a client.”

He wept when informed Weddle was going with him over several larger, California-based agencies. He told his future wife he had just signed a once-in-a-decade client.

The Chargers also saw something unusual in Weddle, trading four picks to draft him 37th overall.

Again he rewarded a team's faith, becoming a full-time starter by his second season and a second-team All-Pro by his fourth. More than that, he became a central figure in the franchise, arriving for work at 4:30?a.m. and teaching younger teammates where they belonged on each down.

NFL friendships are often segregated along offense-defense lines, but Weddle formed a deep bond with Chargers quarterback Philip Rivers — the rare teammate who matched his passion.

“After each series, we'd go and talk. What did you see? What did I see? This is what I did. Why did you do it?” Weddle says. “And then as our families grew up together, our sons played football together. We'd eat together. We're just super close. It is ironic, because I'm a safety and he's a quarterback. But he's just a unique individual. We're brothers, and it will always be that way.”

For all his brilliant moments in San Diego, Weddle was on the wrong end of one of the most famous plays in Ravens history — Ray Rice's fourth-and-29 scamper against the Chargers in 2012.

Weddle was playing deep, anticipating a long heave, and when he saw the short pass to Rice, he thought “This is the dumbest decision [quarterback Joe] Flacco could ever make.”

He darted toward Rice, and when he felt the familiar crunch of contact he assumed he was making the game-clinching tackle. He asked for a recap a few minutes later as he walked to the locker room with teammates. “You got knocked out,” one replied.

The contact he felt was a violent block from Anquan Boldin. The Chargers lost, and the Ravens were on their way to an eventual Super Bowl victory. “Still waiting for my ring,” Weddle jokes of his contribution to their run.

Confidants say he sensed trouble lurking down the line after Tom Telesco became the Chargers general manager in 2013. Though Weddle was perhaps the best safety in the league in 2014, it was clear to him before last season that the Chargers had little intention of offering another long-term deal.

Because he had committed an inordinate amount of his soul to the franchise, it was a bitter realization. Chanel and his parents describe 2015 as a rare period when he did not pulse with his usual joy.

The disconnect became more personal still when the Chargers fined him $10,000 for remaining on the field to watch his daughter perform in a halftime show during a December home game. Then they put him on injured reserve for the final game of the season, though he felt healthy enough to play.

“It was emotional from the standpoint that he gets so attached,” Canter says. “He's a true believer. He was a face of the organization, and they [mistreated] him. I've been doing this for 20 years and I've seen lots of acrimonious breakups. But I've never been in a situation that made less sense to me.”

Starting anew in Baltimore

Weddle's parents often travel to watch him play, and they enjoy tailgating. Last November, they came to Baltimore in their Chargers gear and set up outside M&T Bank Stadium. They expected guff, but instead, the day turned into a mini recruiting session, with fans telling the Weddles how welcome Eric would be should he don the purple and black.

“We looked at each other and said, ‘If he has to leave the Chargers, wouldn't it be great if he came to a town like this?'?” Debbie recalled.

Weddle was attracted not only to the Ravens' Super-Bowl-or-bust approach but to the concern team officials showed for his wife's comfort. Chanel spilled her share of tears at the prospect of uprooting their family, but her husband's instincts had rarely led them astray. And Baltimore felt right.

Weddle knows he'll face comparisons to Reed, and he doesn't recoil from them. The Ravens great and his Pittsburgh Steelers counterpart, Troy Polamalu, were the standard at safety when Weddle came into the league. He studied them on film and sought their input after games.

He says he's probably more like Polamalu because he spends as much time near the line of scrimmage as in deep coverage. Pro Football Focus described him as the “Swiss army knife of safeties.”

But mutual teammate Jarret Johnson sees similarities to Reed. “What made Ed was his ability to trust his instincts and what the film showed him as opposed to what the specific coverage told him to do,” he said. “Weddle's the same way. … He ain't scared to buck coverage to make a play.”

Weddle swears he would never have signed with the Ravens if he could not live up to such standards.

“If I could do half of what Reed did here, I'd be all right,” he said. “But I expect to do great things. I expect to have an amazing season, to be the best in this league and lead this team. Otherwise, I wouldn't be here.”

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE