France to honor retired dairy farmer

Baltimore County WWII veteran, 100, to be named to French Legion of Honor

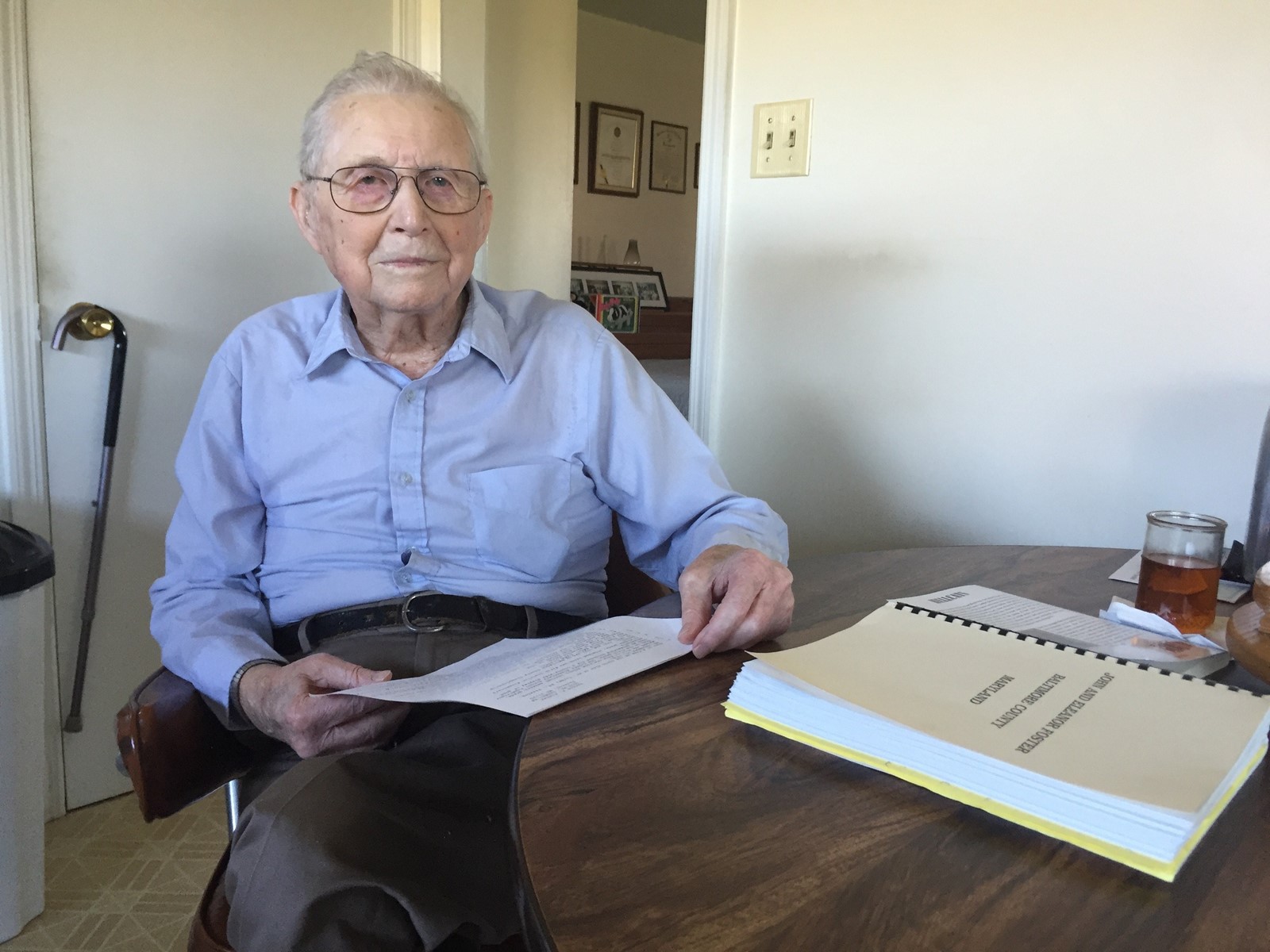

Vernon Foster, a centenarian, World War II tank commander and retired Baltimore County dairy farmer, will be named Tuesday to France’s Legion of Honor.

Foster, 100, fought the Nazis in France and Germany during the war from his Sherman tank “Dottie,” named after his wife.

He’ll receive the French Legion of Honor badge at the French Embassy in Washington, D.C. Established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802, the Legion of Honor is the highest French order of distinction for military and civil merits.

The country has previously honored other American veterans who helped liberate the country from Germany in World War II.

The honor will be bestowed to Foster and four other American World War II veterans just shy of the 75th anniversary of D-Day, when allied forces invaded France’s northern beaches on June 6, 1944, in the Normandy region. The event will be attended by retired Sens. Robert Dole and John Warner and Energy Secretary Rick Perry.

Foster was 26 years old when he landed on the Normandy beaches a few months later on November 20, 1944.

More than 70 years later, Foster is matter of fact about the recognition.

“I probably shouldn’t say this, but I’ve been honored so many times, I have so many plaques I can’t even count them,” Foster said.

But, he added, he’s “always glad to know that other people appreciate” the sacrifice he made during World War II and approaches most honoring ceremonies similarly.

“I guess I take it as it comes,” he said, laughing.

An embassy spokeswoman said any American veteran who can prove they were in France during the war may be awarded the Legion of Honor.

Foster was a lieutenant in the U.S. Army commanding an M-4 Sherman tank. His unit fought intense battles in France’s Alsace region on the German border before pushing deep into Germany, where they fought the Nazis in Herrlisheim and Ludwigshafen.

He commanded a crew that included himself, a gunner, a loader, a driver and an assistant driver.

Foster was a commander and platoon leader with the 2nd Platoon, Company A, 714th Tank Battalion. It was part of the fabled 12th Division that was attached briefly to the command of Gen. George S. Patton Jr.

Foster was hit by German artillery shell shrapnel. Medics pulled most of it out, but he still has a piece of shrapnel behind an eye.

Rick Scavetta, a journalist with the Aberdeen Proving Ground News, wrote about Foster’s military history in 2016. He said interviewing Foster is like “seeing a piece of living history.” He visited Foster at his home in Baltimore County, where he said Foster has a table with 200 letters that his wife Dottie wrote him in the war and another 200 that he wrote her.

Stephen Belkoff, who met Foster about 10 years ago through the Third Gunpowder Agricultural Club, noted the clarity of Foster’s memory.

“His mind is incredibly sharp. He has attention to details — things people shouldn’t remember,” said Belkoff, a mechanical engineering professor at the Johns Hopkins University. “I’m a big fan of history, so the guy’s a walking textbook. So I’d rather listen to him than read a book at the library.”

Belkoff said Foster’s recognition is well overdue.

“He was part of what’s called the Ghost Division,” Belkoff said. “A lot of what he and his group did didn’t get officially recognized because they weren’t supposed to exist.”

Foster

“Most guys wanted to go because they had heard so much about what Hitler had done.

“It’s like if you’re going out to plant corn,” the lifelong Parkton farmer said. “You just do it.”