People seen through environments

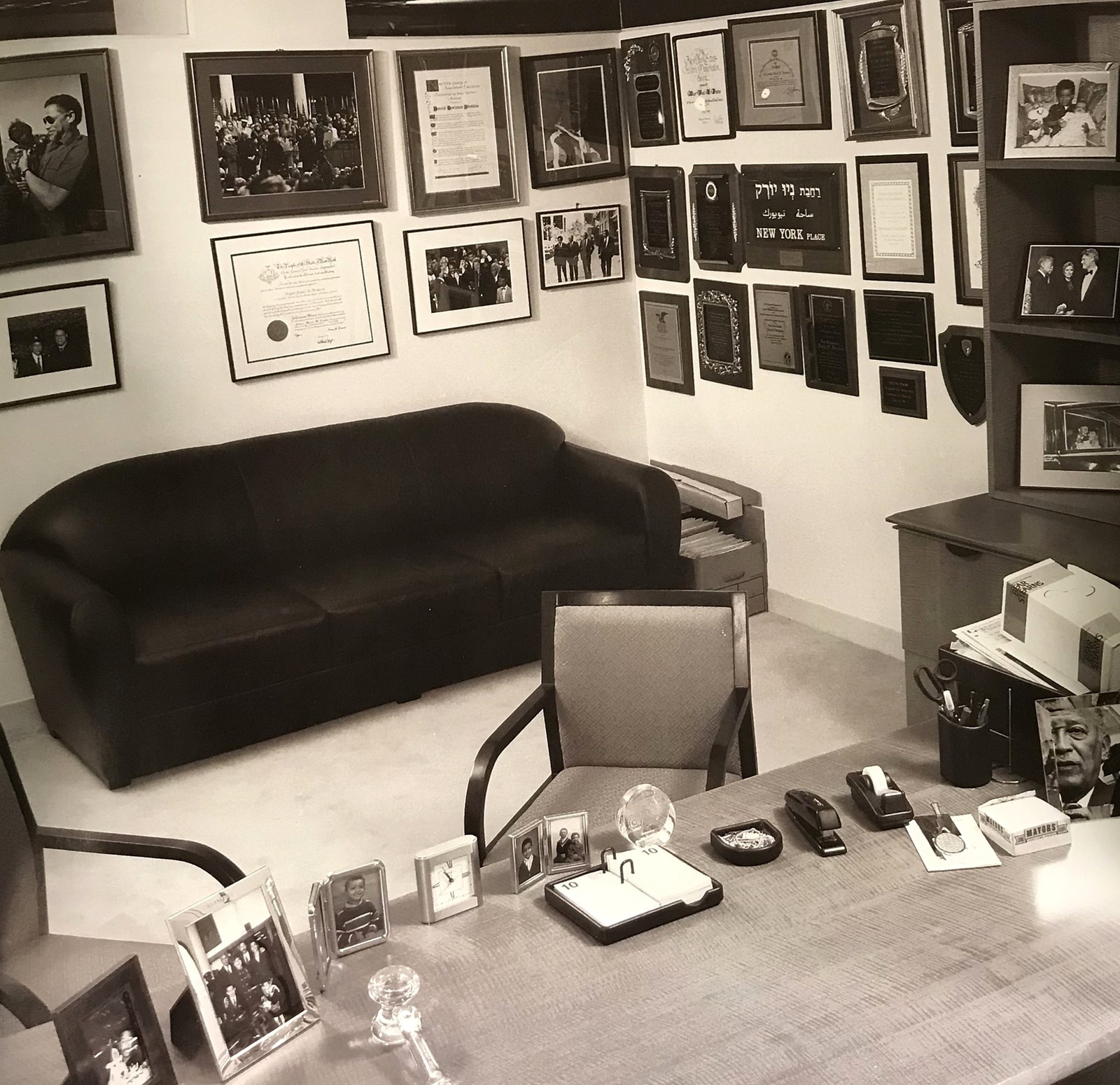

Given the barrage of criticism he faced, it seems natural that David Dinkins, the first black mayor of New York, would literally erect a barrier between himself and the visitor sitting on the opposite side of his desk.

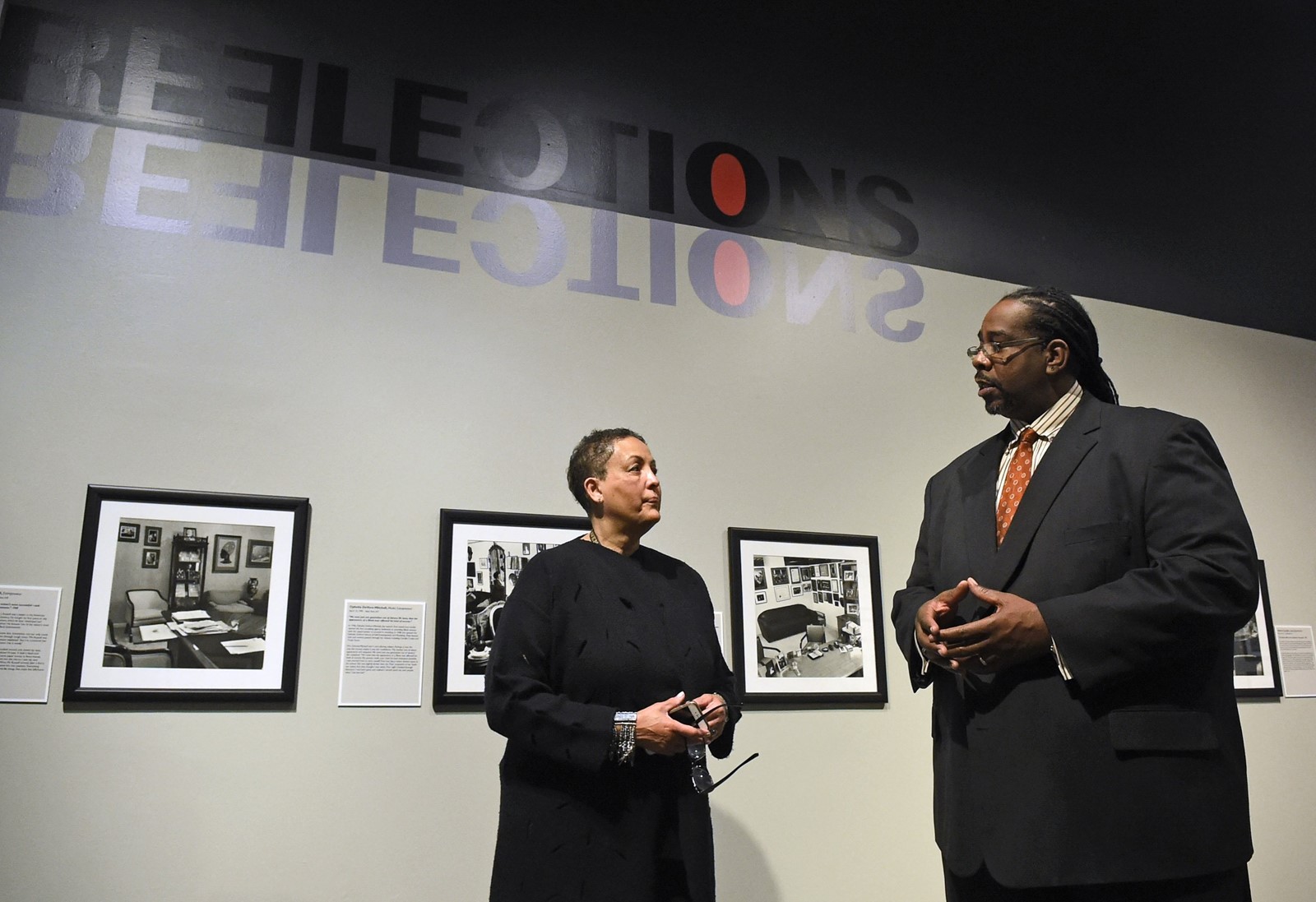

The artist Terrence A. Reese shot a black-and-white photograph of Dinkins’ office that’s included in a fascinating exhibit that’s running for five more months at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture.

“Reflections: Intimate Portraits of Iconic African Americans” consists of 45 documentary-style images of the places where iconic African-American groundbreakers lived and worked. As seen through Reese’s lens, the result is a series of incisive psychological portraits of such figures as the civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson, legendary blues musician B.B. King, the media entrepreneur Cathy Hughes — and Dinkins.

“People know the public persona of famous individuals,” said Charles Bethea, the Lewis’ chief curator. “What TAR [Reese] was trying to do was to engage with them in a unique way, by photographing their environments. The things we collect, what we put on our walls and tables, make us who we are.”

For example, visitors to Dinkins’ office were separated from the former mayor by an array of objects lined up at the perimeter of his desk like an army formation. A mirror, notepad, pencil case, tape dispenser, stapler, paper clip tray, desk calendar, clock and several framed photographs were arranged side by side and just a few inches apart. Visitors dare not get too comfortable; there’s no place to put down a pad of paper or coffee mug.

If the desk projects an aura of defensiveness, perhaps that’s because Dinkins was New York’s mayor during the Crown Heights riot of 1991, which pitted the black population of Brooklyn against Orthodox Jews. Dinkins was pilloried for what was perceived as the city’s ineffective police response. He lost his re-election bid two years later, and the defeat was widely attributed to the uprising.

Reese shot his subjects entirely in black and white because, Bethea said, he was attempting to draw viewers into his images. By avoiding the hyper-stimulation caused by bursts of color, Reese encourages his audience to linger. In addition, each photograph is 16 inches square, a smaller size that coaxes visitors to step forward and scrutinize details.

“Some of these environments are dense with objects,” Jackie Copeland, the museum’s director of education and visitor services, said. “We’re always trying to slow museum visitors down. We don’t want this to be a shopping mall experience.”

Each leader whom Reese photographed is also physically present in the photo in the form of a small mirror reflection. Museum goers quickly get lured into playing a “Where’s Waldo” game of locating the flesh-and-blood man or woman. In some cases, the reflection is simple to spot. Other portraits, however, especially those containing dozens of picture frames, will challenge even the sharpest eyes.

Nor was Reese above having a bit of fun with his audience, especially when the subject was willing. Just try to figure out where Gordon Parks was standing when Reese took a snapshot of Parks’ pleasantly cluttered Manhattan living room. We’ll give you one clue — he’s not where you think he is. The large book on the table in the foreground so invitingly opened to an image of a distinguished-looking, mustachioed gentleman contains a photograph of the legendary filmmaker, not his mirror reflection.

According to the accompanying wall text, it was Parks who suggested the addition of the coffee table book, telling Reese mischievously, “Let’s mess with them.”

Bethea has arranged the portraits roughly by profession, with business leaders in one intimate grouping; educators, physicians and social workers in another, artists in a third.

Bethea was struck by entrepreneurs’ preference for tranquil surroundings with relatively few objects. Distractions are kept to a minimum — a seeming antidote to the frantic pace of these executives’ working lives. For example, the philanthropist and management consultant Reginald Van Lee appears to have lived on the upper floor of a luxury high-rise apartment building. Furniture lines the walls, leaving an uninterrupted expanse of light-colored carpet in the center. This visually forms a path leading guests to a bank of floor-to-ceiling windows with a panoramic view of rooftops. It’s apparent at a glance that the apartment’s occupant was preoccupied with envisioning the future.

Contrast that with the artists.

Reese photographs just a few square feet of the home of the jazz saxophone player and composer Jimmy “Little Bird” Heath. But that compact area is cluttered with hundreds of objects — though dominated by just one, the piano where Heath works. Columns of CDs as tall as a grown man flank the piano, while a third pile has begun to grow beneath the keyboard. In contrast, the room’s walls, top of the piano and fallboard (the case covering the keys) are jam-packed with family photos.

Is there a better visual depiction of the opposing forces that compete for an artist’s time and emotional energy -- music, and the people he loves?

Images like those that Reese has shot during a 10-year period build on the traditions of Renaissance portraiture, Copeland said.

“If you wanted to show off your wealth and status, you would commission a portrait of you situated in your surroundings,” she said. “If you were well-read, books would be in the painting. If you were well-traveled, there would be a globe. Everything in the artwork would point to your status and station in life.”

She noted that all portraits reveal as much about the viewer as they do the sitter. For example, in Reese’s photo of the Rev. Jesse Jackson, nearly the entire body of the activist is reflected in the large mirror hanging above the desk. Jackson is leaning on the door frame, his face wearing his trademark scowl. The civil rights leader is standing behind his son, Jesse Jackson Jr., who is seated at a desk with his back to the viewer, working the phones.

One observer might note that Jackson’s reflection is much larger than the reflections in Reese’s other photos and interpret the image as symbolizing Jackson’s tendency to seek the spotlight.

Another viewer might focus instead on the running shoes in the lower left-hand corner of the frame — a pair of sneaks that, due to a trick of perspective, appear as though they were worn by giants. That viewer, noting how the image of the older man looms over the younger, might conclude that Jackson Jr. had big shoes to fill.

“ ‘Reflections’ gives us an opportunity to have those kinds of discussions,” said Wanda Q. Draper, the Lewis’ executive director.

She admits that when Bethea proposed the photography exhibit, her initial response was lukewarm; a bunch of monochromatic photographs of unoccupied rooms didn’t strike her as a can’t miss crowd-pleaser. Then, Reese’s photos arrived and went up on the walls, and Draper found herself making excuses to visit the gallery.

“Once I started looking at them,” she said, “I couldn’t stop.”

After exploring Terrence A. Reese’s photographs of African-American leaders, check out the companion show in the next gallery. The main exhibit focuses tightly on African-American pioneers who helped shape a nation. In contrast, “Reflections of Baltimore” centers on a place. The smaller gallery displays about two dozen paintings, prints and photographs created by local artists. The lineup will change periodically.

“This is an opportunity for people in the community to come in and literally reflect on Baltimore, the good and the not so good,” said Copeland.

March features photographers Shan Wallace, Kyle Pompey, Reginald “Reggie” Thomas and the photographer who goes by the name “Mr. Freeze.”

The next rotation will showcase painters from the Maryland Institute College of Art and will go on view April 7. They include Tyler Ballon, Mark Fleuridor, Andrew Gray, Moses Jeune, Destiny Belgrave and Monica Ikegwu.